By Claudia Moscovici

In his new book, Palestine 1936: The Great Revolt and the Roots of the Middle East Conflict (Rowman & Littlefield Publishing, New York, 2023), Oren Kessler traces the roots of the ongoing conflict between Palestinians and Israelis back to the Arab revolts of 1936-1939 against the influx of Jewish immigration as well as against colonial rule by Great Britain: in other words, to the crucial decade before the foundation of the state of Israel in 1948 (and what the Palestinians view as “Nakba”, or the “catastrophe” of losing their autonomy and homeland). Kessler offers readers a deeper understanding of the conflict that pervades news about the Middle East to this day by recounting the story “of two nationalisms, and of the first major explosion between them. The rebellion was Arab, the the Zionist counter-rebellion—the Jews’ military, economic, and psychological transformation—is a vital, overlooked element in the chronicle of how Palestine became Israel” (Palestine 1936, 2). Unlike other notable books about this longstanding conflict, such as Micah Goodman’s Catch-67, Noa Tishby’s Israel: A Simple Guide to the Most Misunderstood Country on Earth, or, for a perspective more sympathetic to the Palestinian cause, Mehran Kamrava’s The Impossibility of Palestine, Kessler’s Palestine 1936 presents the historical origins of the Palestinian-Zionist conflict in as impartial, nonjudgmental and noneditorializing a manner as possible, without attempting to cast blame, exculpate, justify or even propose viable solutions.

What emerges from Kessler’s study of this controversial and much-debated subject is a richer and fuller picture of how and why the Palestinian-Zionist conflict became something very close to a zero-sum game well before the establishment of the state of Israel. Consequently, Palestine 1936 also helps explain why this conflict goes on so heatedly to this very day and why even good-faith efforts to end it largely fail. In game theory, a zero-sum game describes any situation where gaining advantage by one side entails an equivalent loss by the other side. Zero-sum games are the exception not the rule in politics. When countries go to war, their conflict is often described by their rulers or leading ideologues as a zero-sum game in order to simplify complex socio-political circumstances and rile people up emotionally into demonizing the other side, so that they are more likely to blindly fight “the enemy”. Yet, in actuality, most wars or political tensions are not a zero-sum game and, as successful international diplomacy and negotiations amply illustrate, often both sides stand to gain from peace, economic relations and stability.

Unfortunately, the Palestinian-Zionist conflict—I call it that because, as indicated, it preexisted the establishment of the state of Israel—is not one where negotiations have been very successful. The best way to illustrate a zero-sum game between two peoples making claim to the same strip of land is not by showing the worst elements of both peoples (such as terrorists or bigots), but rather the way Oren Kessler does it in Palestine 1936: by focusing on historical leaders from both sides who represent the best of both societies and who make genuine, good-faith attempts to find peaceful solutions for their people. Although Palestine 1936 covers many of the leaders for both the Palestinians and the Zionists, in my estimation the most notable figures, which I’ll focus on in this review, are the Palestinian intellectual and Assistant Attorney-General of Palestine under the British Mandate, Musa Alami, and his Jewish Zionist counterpart and future first prime minister of the State of Israel, David Ben-Gurion, with whom Alami had several friendly, earnest discussions about how to best accommodate both Palestinians and Jews in Palestine. Before we delve into the nature of their (largely failed) attempts to offer a mutually satisfactory solution, I’d like to first briefly summarize for the general reader the situation in Palestine during the period of time depicted by Kessler in this book.

Between 1936-1939, Palestinians led a series of popular uprisings and worker strikes that is referred to as “the Great Revolt” against the British colonial administration, pushing for political autonomy and an end to the open-ended and growing Jewish immigration as well as against Jews buying Palestinian land in order to establish a larger Jewish presence (and, later, their own state) in Palestine. Before the Jewish mass immigration, which increased with a great sense of urgency with the rise of European Fascism, Palestinians and Jews got along pretty well. Jews were a small minority in Palestine. A significant spark of the conflict between them was the Balfour Declaration of 1917, issued by the British Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour in a letter to the prominent Jewish leader and banker Lord Rothschild, in which the latter announced British support for a “national home for the Jewish people in Palestine”. In part with this British support—which, incidentally, was not unwavering or without its own contradictions–over the course of the next two decades, Jewish immigration to Palestine increased to the point where Jews comprised 1/3 of the total population of Palestine by the mid 1930’s. That posed a serious problem for the Palestinians. The 1936 revolt was sparked by a dramatic increase in Jewish immigration in 1935, from 57,000 to 320,000 Jews. There were two phases in the Great Revolt, which had different focal points and leaders. The first phase, which began in April 1936, was largely organized by the urban leaders and the Palestinian elite and manifested itself primarily in strikes and politial protests. By October 1936, the British administration defeated this uprising using both the carrot and the stick: they offered some political concessions (talks of a slowing down of Jewish immigration and greater native autonomy) and as well as issuing threats of imposing tougher repressive measures, such as martial law. As things didn’t change much following the first revolt, a peasant revolt followed in late 1937, which was suppressed by the British administration.

Kessler’s book reveals that the most influential leaders in Palestine at the time tended to be mediating figures between the West and Palestine: Western-educated Palestinian leaders, such as Musa Alami, who often acquired positions of power within the British colonial administration in Palestine yet at the same time had a deep understanding of and loyalty to their people. Despite their distrust of Zionism, these Palestinian leaders were usually not anti-Semites. In a telling anecdote, Kessler recounts that Faidi al-Alami, the Mayor of Jerusalem and Musa Alami’s father, said to a Jewish Zionist acquaintance visiting him from Berlin: “It’s not true that we opppose the Jews moving here… On the contrary, the Jews are wanted—they’re a stimulating, fermenting, progressive force. The question is one of numbers. They are like salt in bread—a small amount is vital, but a large amount is even worse than none at all” (Palestine 1936, 9). It was the mass immigration of Zionists, he argued, not the fertile intermingling of Arab and Jewish cultures, that caused major concern for Palestinians. According to Kessler, his visitor confirmed his fears by retorting that Jews didn’t want to be the salt, but the bread itself in Palestine. For Zionists, Jews, increasingly discriminated against and mistreated in Germany and throughout the world, were in urgent need of their own homeland in Palestine. Their survival depended on it. This small snippet of a conversation already sketches the outlines of something close to a zero-sum game between Jews and Palestinians in Palestine.

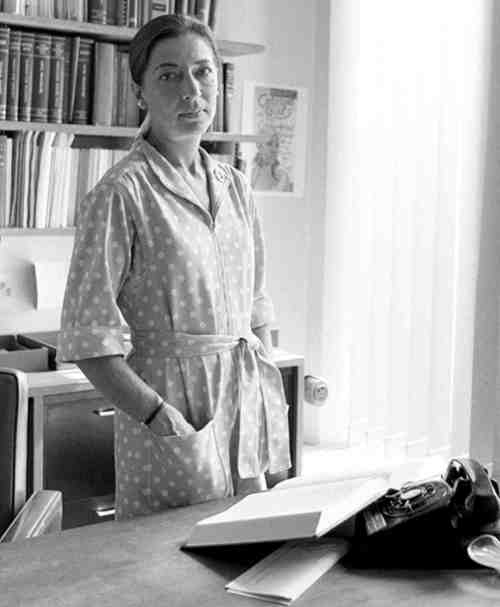

Musa Alami attempted to find solutions to this problem. Cultured, multilingual, almost universally respected and liked by Palestinians, Jews and the British, he was educated at the American Colony as well as at the French language Ecole des Freres. He subsequently studied law at the University of Cambridge, which enabled him to become the private secretary of the High Commissioner of Palestine, Arthur Grenfell Wauchope. The latter trusted him to the point that whenever anyone gave him a report that contradicted Alami’s, he famously retorted, “Musa tells me otherwise” (Palestine 1936, 35). Alami met several times with his Jewish counterpart, David Ben-Gurion, and even discussed with him the possibility of something resembling a two-state solution in Palestine, with Jews inhabiting a part of (what would become) Tel Aviv in a Muslim majority Palestine. He was quite firm, however, that Palestine belonged primarily to the Palestinians, making it clear to Ben-Gurion that he did not approve of Arabs selling Palestinian land to Jews. Ben-Gurion recounted that Alami told him that he would have preferred to leave Palestine undevelloped for another hundred years until the Arabs could develop it themselves rather than sell it even at advantageous, high prices to Jews. That was the pivotal moment when Ben-Gurion, who understood and sympathized with Alami’s perspective, realized that they had reached an impasse not only in their discussions, but also, more importantly, between their people.

Ben-Gurion himself was a man of immense talents and a visionary. He was born in Russian-ruled Poland and immigrated to Palestine in 1906. He rose to prominence rather quickly and, from 1935 to 1948, became the de facto leader of the Jewish community and, once the state of Israel was established, its first prime minister. Well educated and a polyglot, Ben-Gurion had a deep loyalty to the Jewish people and commitment to establishing their own state in Palestine. What distinguished him most from many other Zionists, however, was his ability to empathize with the Palestinians and describe things to his own community from their perspective. Kessler recounts how in meetings with other Jewish leaders, Ben-Gurion would say “‘I want you to see things for a moment with Arab eyes…. They—the Arabs—see things differently, exactly the opposite of what we see’” (159). He would try to get his peers to understand the other side’s position without demonizing, caricaturizing or in any way reducing the humanity of the Palestinians: “‘There are two peoples’ in Palestine, he declared, drawing out the words for emphasis. ‘The Arabs are not to blame if they do not want this country to stop being Arab… our enterprise is aimed at turning this land into a Jewish one’” (160). The impasse reached by Alami and Ben-Gurion in their attempts to find viable solutions for their people is very telling. If even well intentioned leaders and diplomats continue to grapple to this day with the problems identified by these early, visionary Palestinian and Jewish leaders, which are described so thoroughly and dispassionately by Oren Kessler in Palestine 1936, it’s because Palestinians and Jews continue to struggle with the same (close to) a zero-sum game between two peoples that both have good reasons to claim rights to the same tiny strip of land.

Young Zionists Unite: Bryan Leib’s new pro-Israel “Tribe”, HaShevet

Young Zionists Unite: Bryan Leib’s new pro-Israel “Tribe”, HaShevet