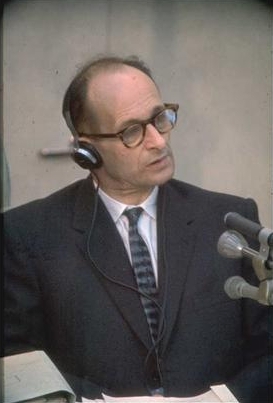

Adolf Eichmann during trial, Wikipedia Commons

Review by Claudia Moscovici, author of Holocaust Memories: A Survey of Holocaust Memoirs, Histories, Novels and Films (Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, 2019)

https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/076187092X/ref=ox_sc_saved_title_3?smid=ATVPDKIKX0DER&psc=1

The wonderful new movie, Hannah Arendt (2012), directed by Margarethe von Trotta and starring Barbara Sukowa, shows that Arendt’s series of articles on Adolf Eichmann’s trial, covered by The New Yorker in 1961 and subsequently published under the title of Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil (Penguin Books, New York, 1963), was a double-edged sword in her career. On the one hand, it gave Arendt a broader mainstream visibility, in part because of the international controversy it generated. On the other hand, this very controversy cost her several valuable friendships and even jeopardized her reputation in the academia. The controversy hinges upon the manner in which Arendt describes the nature of evil that characterizes the worst genocide in human history: the Holocaust.

Her explanation, captured by the phrase “the banality of evil,” posits that evil deeds are, for the most part, not perpetrated by monsters or sadists. Most often, they are perpetrated by seemingly ordinary people like Adolf Eichmann, who value conformity and narrow self-interest over the welfare of others. The concept of the banality of evil seems intuitive enough. Nontheless, it generated a huge controversy, primarily because critics interpreted it as exonerating Adolf Eichmann and indicting the victims of the Holocaust: particularly the Jewish leaders who were compelled by the Nazis to organize the Jewish people for mass deportations and eventual extermination.

Was Arendt putting the criminals and the victims in the same boat? Or, even worse, does her notion of the banality of evil end up blaming the victims? I don’t think so. In what follows, I’d like to explain why by outlining Arendt’s two explanations of the banality of evil: the first one being people who naturally lack empathy and conscience in any circumstances (like Eichmann) and who thrive in totalitarian regimes; the second understood as evil actions (or callous indifference) that even people who do have a conscience are capable of under extreme circumstances.

1. Adolf Eichmann and the banality of psychopathy

Adolf Eichmann (1906-1962) was a Lieutenant Colonel in the Nazi regime and one of the key figures in the Holocaust. With initiative and enthusiasm, he organized the mass deportations of the Jews first to ghettos and then to extermination camps throughout Nazi-occupied Europe. Once Germany lost the war, he fled to Argentina. Years later, he was captured by the Mossad and extradited to Israel. In a public trial, he was charged with crimes against humanity and war crimes. He was found guilty and executed by hanging.

In her accounts of the trial, Arendt is struck by the contrast between Eichmann’s monstrous deeds and his average appearance and banal, technocratic language. Unlike other Nazi leaders notorious for crimes against humanity, such as Amon Goeth or Josef Mengele, Eichmann didn’t seem to be a disordered sadist. More remarkably given his actions against the Jewish people, unlike Hitler, Eichmann wasn’t even particularly anti-Semitic.

Although six psychiatrists testified during the trial to Eichmann’s apparent “normality,” in her articles Arendt emphasizes the fact that his normalcy is only a mask. In fact, she highlights the aspects of his behavior under questioning that were anything but normal: his self-contradictions, lies, evasiveness, denial of blame about the crimes he did commit and inappropriate boasting about his power and role in the Holocaust for crimes there’s no evidence he committed. Arendt is particularly struck by this man’s absolute lack of empathy and remorse for having sent hundreds of thousands of people to their deaths. To each count he was charged with, Eichmann pleaded “Not guilty in the sense of the indictment.” (p. 21) This leads Arendt to ask: “In what sense then did he think he was guilty?” (p. 21) His defense attorney claimed that “Eichmann feels guilty before God, not before the law,” but Arendt points out that Eichmann himself never acknowledges any such moral culpability.

If he denies any moral responsibility it’s because, as Arendt is astonished to observe, he doesn’t feel any. Although, surprisingly enough, none of the forensic psychologists see Eichmann as a psychopath, Arendt describes Eichmann in similar terms Hervey Cleckley uses to describe psychopathic behavior in his 1941 groundbreaking book, The Mask of Sanity. First and foremost, Eichmann is a man with abnormally shallow emotions. Because of this, he also lacks a conscience. Even though he understands the concept of law, he has no visceral sense of right and wrong and can’t identify with the pain of others. His extraordinary emotional shallowness impoverishes not only his sense of ethics, but also his vocabulary. Arendt gives as one of many examples Eichmann’s desire to “find peace with his former enemies” (p. 53). Arendt states that “Eichmann’s mind was filled to the brim with such sentences” (p.53). These stock phrases are a manifestation of Eichmann’s empty emotional landscape; his behavior towards the Jews even more so.

It is surprising to me that in a review of Hannah Arendt the movie that also focuses on Eichmann in Jerusalem, Mark Lilla believes that Hannah Arendt was duped by Eichmann’s mask of sanity. He argues that Arendt’s search for a more general explanation of evil blinded her to Eichmann’s particular disorder: “But the other impulse, to find a schema that would render the horror comprehensible and make judgment possible, in the end led her astray. Arendt was not alone in being taken in by Eichmann and his many masks, but she was taken in.” (Mark Lilla, “Arendt and Eichmann: The New Truth,” The New York Review of Books, November 21, 2013). In her description of Adolf Eichmann as a man without conscience and empathy, I didn’t see any evidence that she was duped by him in the same way the psychiatrists testifying at his trial obviously were.

Yet, Arendt emphasizes, even ordinary people capable of empathy and remorse can still cause extraordinary harm in unusual circumstances. This constitutes the second understanding of the banality of evil she develops: namely, the banality of conformity, which is what I’ll cover next week.

Claudia Moscovici, Literaturesalon