Review by Claudia Moscovici, author of Holocaust Memories: A Survey of Holocaust Memoirs, Histories, Novels and Films (Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, 2019)

https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/076187092X/ref=ox_sc_saved_title_3?smid=ATVPDKIKX0DER&psc=1

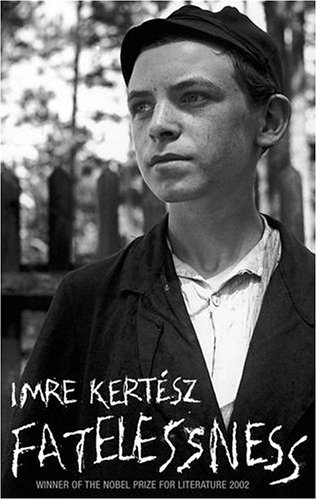

When Luisa Zielinski interviewed the Hungarian writer, Nobel Prize winner (2002) and Holocaust survivor Imre Kertesz in the Paris Review during the summer of 2013, the author was already suffering from Parkinson’s disease. (See Imre Kertesz. “The Art of Fiction”, Paris Review No. 220, interviewed by Luisa Zielinksi) Despite being seriously ill, Kertesz spoke with characteristic lucidity about his fiction as well as about the Holocaust. Born in 1929 in Budapest, Kertesz was deported to Auschwitz in 1944 for a short period of time, and then transferred to Buchenwald. His works deal with the Holocaust, yet they are not strictly speaking autobiographical. Fatelessness (Vintage International, 2004) in particular seems to parallel Kertesz’s experiences in Nazi concentration camps, but the author focuses on the subject’s historic-philosophical dimensions. Kertesz views his description of the Holocaust in Fatelessness as a rupture of civilization that the entire world should examine and take seriously rather than an anecdote of his own trying experiences during adolescence. “I was interned in Auschwitz for one year,” he recalls. “I didn’t bring back anything, except for a few jokes, and that filled me with shame. Then again, I didn’t know what to do with this fresh experience. For this experience was no literary awakening, no occasion for professional or artistic introspection.” Writing as a mode of reflection and communication with others rather than in order to come to terms with his painful personal experiences assumed, at some point, primary importance for him.

Yet, as Kertesz recounts during the Paris Review interview, he didn’t feel destined to be a writer. Rather, he became a writer by painstakingly editing his own texts. The process of writing wasn’t easy, both because of the difficult subject matter he chose and because he had to hide his endeavors from the Communist regime. In fact, the experience of totalitarian repression forms a common thread between his experience of Nazism and of the repressive regime that followed it. “I was suspended in a world that was forever foreign to me, one I had to reenter each day with no hope of relief. That was true of Stalinist Hungary, but even more so under National Socialism,” he declares.

Despite the broad socio-political sweep of his themes, Kertesz’s fiction, particularly the novel Fatelessness, reads like an intimate psychological account of a young man’s disconcerting and painful experience of being uprooted from his family, schoolmates and friends to be thrust into the alien and brutal world of the Nazi concentration camps. Gyorgy Koves, the 15-year old protagonist, first loses his father, who is deported to and dies in labor camp. His stepmother and a Hungarian employee continue taking care of the family business, a store, and are fortunate enough to survive the war and eventually marry each other. But Gyorgy (George) lacks such luck. Along with a throng of teenage boys, he’s rounded up by the Hungarian Arrow Cross and sent to forced labor, then deported to Auschwitz. Fatelessness depicts his experiences there.

There are countless books on the Holocaust. The subject has been written about so much that some readers risk being jaded to it. This novel is especially effective in rendering this familiar topic new and touching. One of the most unique aspects of the novel is its present temporality: the adolescent narrator describes his experiences in the present, as if writing in a diary, noting every character’s expression and interspersing realistic dialogues without offering much judgment or analysis. Kertesz considers this observational technique as appropriate for a child narrator. As he explains, “a child has no agency in his own life and is forced to endure it all”. While few Jewish victims had much agency during the Holocaust, adults at least had the emotional maturity to realize what was happening to them and understand some of the socio-political reasons why. Child victims, on the other hand, were swept by the Nazi extermination machine without being able to comprehend the events that destroyed their lives or do anything about it. Given the almost existentialist nature of Kertesz’s writing, how much of Fatelessness is based on the author’s life and how much of it is historical fiction becomes far less relevant than the narrative’s powerful and immediate connection to generations of readers.

Claudia Moscovici, Holocaust Memory